Premillennialism

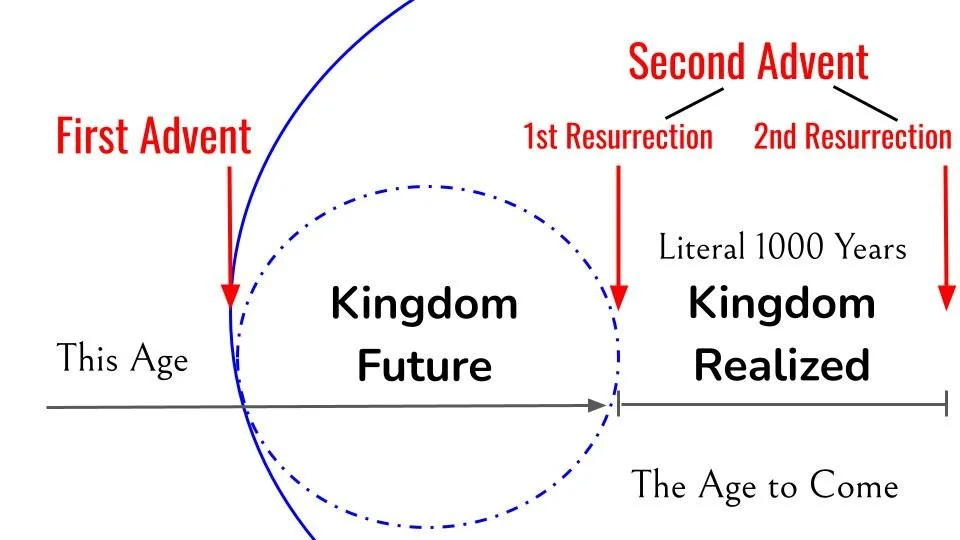

Here we are examining historic premillennialism. This is not to be confused with dispensational premillennialism, which I have written about elsewhere in terms of its basic tenets, its historical roots, its central doctrine that divides Israel and the church, and its treatment of Daniel 9:24-27. While the two views share the conviction that there will be a literal thousand year reign of Christ on earth after the rapture, their fundamental rationale for that is quite different.

The historic position has also benefited greatly from the excellent biblical theological reflection of George Eldon Ladd in the twentieth century. For Ladd, the kingdom has been inaugurated in Christ’s First Advent, so that there is a “presence of the future.” In other words, the same “this age” and “age to come” dichotomy articulated by the biblical theologians cited by the Reformed—Vos, Ridderbos, et al—is used here by Ladd to speak of the simultaneous presence of the age to come with this age. He says: “if the works of Jesus are signs of the nearness of the Kingdom and not of its actual presence, we cannot avoid the theological problem which casts Jesus’ entire message and mission under a cloud.”1

The focus is on the Person and work of Christ in His two advents:

“before the eschatological appearing of God’s Kingdom at the end of the age, God’s Kingdom has become dynamically active among men in Jesus’ person and mission. The Kingdom in this age is not merely the abstract concept of God’s universal rule to which men must submit; it is rather a dynamic power at work among men.”2

We see this in Ladd’s treatment of the binding of Satan. He recognizes the link Jesus makes to the coming of His kingdom; but for Ladd, this demonstration of power is simultaneously a decisive “conquest over the devil,” and yet not a “complete defeat of Satan.”3 Of course the other views would agree to these words, but often the differences are matters of degrees.

There is a strong link between pessimism and Christ’s initiation.

Ladd sees one of the main characteristics of the authors of the apocalyptic genre to be pessimism, rightly defined: “it is erroneous to call the apocalyptists pessimists in their ultimate outlook, for they never lost their confidence that God would finally triumph … however … [they] reflect pessimism about this age … The solution to the problem of evil was thrown altogether into the future.”4 We can see how this leads directly to the necessity of divine intervention. Something decisive coming from Christ alone can deliver the kingdom to earth.5

Either the second coming is divided into two parts, or we must say in all honesty that this teaches a second and a third advent of Christ. The two events stretched out are the rapture and then after the millennium, the Glorious Appearance. So “the first resurrection” corresponds to the rapture, and “the second resurrection” to the raising of the body and soul of all after this thousand years. This is their surface answer to John 5:28-29.

Although both premilennialist and postmillennialist share the same belief in a literal millennium, the nature of the kingdom is very different for the premillennialist. First, Christ will physically reign from Jerusalem; Second, the age begins with a total consolidation of Christian power. And contrary to both of the other two positions, where the premillennialists speak of an inaugurated kingdom, they do not mean the millennial kingdom. The millennial kingdom and consummated (or, perhaps better, “fully realized”) kingdom are equivalents in this sense.

Important Texts

Revelation 20 is obviously foundational. Just as obviously, there is a consistent chronological assumption. Or is it consistent? What does one do with the other second coming passage in Revelation 11, or the wider scope of history covered in Revelation 12? Not to mention the much more awkward (because of its close proximity to the text) details of Revelation 18 and 19. Is not Babylon already fallen before this return of Christ? And in that return, is not Jesus depicted on the white horse and as if He is executing the full judgment then and there? Nevertheless, the rationale is relentless. The most natural reading of Revelation is the strictly chronological, so that if one does this, then quite obviously Christ returns before this millennium and so forth.

We can at least allow that Revelation 20 is not the only text that Premillennialism is based upon. One may disagree with their exegesis of other passages; but it is a straw man to confine their case only to that one chapter in Revelation.

We have already examined Matt 19:28; 25:31; and Acts 1:6 in the context of dispensationalism. But even if one does not think that such texts demand an exclusively Jewish kingdom, it is still a tangible throne that Christ sits upon on earth. So Revelation 5:10 says the He “hast made us unto our God kings and priests: and we shall reign on the earth.”

And there are key Old Testament passages. Note that many of these will be the same passages cited by postmillennialists. Yet there will be a kind of process of elimination logic here.

Isaiah 65:20. “No more shall there be in it an infant that lives but a few days, or an old man who does not fill out his days, for the child shall die a hundred years old, and the sinner a hundred years old shall be accursed.” Of this Michael Vlasch writes,

“Now we must ask the question, ‘When will these conditions described in Isa 65:20 take place? Can it be during our present age? The answer is clearly, No. We live in a day where people live between 70-80 years on average (see Ps 90:10). If a person dies today at age 100 we say he lived a long life, not a short one. So will Isa 65:20 be fulfilled in the coming eternal state? The answer again must be, No. In the eternal state there is no longer any sin, death, or curse (Rev 21:4; 22:3), so no one will by dying.”6

Zechariah 14:4, 9. “And his feet shall stand in that day upon the mount of Olives … the LORD will be King over all the earth.” Grudem says much the same about this verse as Vlasch said of the Isaiah passage:

It “does not fit the present age, for the Lord is King over all the earth in this situation. But it does not fit the eternal state either, because of the disobedience and rebellion against the Lord that is clearly present.”7

Psalm 72:8-14 has some of these same features.

Proponents

Early Church Fathers such as Papias, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Hippolytus, Apollinaris, Commodian, Lactantius, and Victorinus would all be on the list.8 Although I am not entirely sure one would want to claim Apollinaris except to further establish the widespread belief in that time.

At the end of the sixteenth century, Johannes Piscator and Johann Alsted both embraced a kind of premillennialism that even held the martyrs to be raised with Christ in heaven, with the rest remaining in the tombs until the Last Day, clearly from the Revelation 20 text.9

Early Modern thinkers embracing a form of it include pietists like Jacob Bohme, Jacob Spener, and even the scientist Isaac Newton, who devoted much thought to prophetic speculation.

Adherents of historic premillennialism in the past century would include J. Oliver Buswell, George Eldon Ladd, Millard Erickson, and Craig Blomberg. Many in recent generations have even held to a dispensational form of premillennialism, even while not being known for being champions of the whole system. We might think of Francis Schaeffer, Gleason Archer, James Montgomery Boice, Norman Geisler, and Wayne Grudem.

Criticisms and Potential Responses

1. Premillennialism involves one (or more) direct contradictions to the Lord’s teaching that no one but God knows the time.

Turretin put it in this way:

“If Christ were to come a thousand years before the end of the world, the end of the world would be known and the time of the final advent of Christ. However Christ expressly testifies that this was unknown to all creatures and even to the Son of man.”10

A response is not difficult to imagine: Jesus’ statement in Matthew 24:36 (Mk. 13:32) only speaks of the rapture and not the physical Second Coming. To answer this, one must appeal both to the immediate context of those passages, as well as to the texts linking the Second Coming to the general resurrection of both the righteous and the wicked. 2 Peter 3:10-12 makes this particular awkward. Within the same general context of not knowing the exact time—that is Peter’s whole premise in demanding that we live a certain way in the meantime—he describes the coming the Christ to involve an immediate and universal burning up of the universe. In fact the words are repeated in back to back verses here. This leaves room for neither a seven year tribulation period, nor even for a thousand years of interim between rapture and final judgment.

2. Premillennialism holds to an awkward “mongrel” kingdom.

That phrase comes from Boettner,11 but hopefully we get the idea. How exactly will glorified saints and cursed bodies intermingle? Additionally, aren’t there passages teaching that “flesh and blood” will not be in the kingdom? Someone may reply that this is not the same thing as that kingdom. At first the Premillennialist told us the same about the inaugurated kingdom. Now not even the realized kingdom is that kingdom. The basic trouble here is that one strains the meaning of the passages talking about the future kingdom to continue dividing up its realization. It is not strictly illogical that people will live the entire time, while others die; that some are glorified in some sense, while others are not. Logically possible, yes; probable given the data of Scripture? It strains the imagination.

3. Premillennialism demands that Satan will be loosed while Christ is reigning and ruling on earth, or else that Christ is temporarily removed.

Why Satan should be loosed and Jesus should come back to judge, after already being present on earth to rule for those thousand years, is never satisfactorily explained by any Premillennialist I am aware of. Please note that I am not suggesting that it is logically impossible, nor even am I arguing from the basis of the devil being let loose at the end (since all millennial views believe a form of this); but rather the question is purely a request for any text or set of texts that might give any indication that this will be the case, or why it would make any sense.

Some have evidently considered this and factored it into their view. Bavinck reported,

“Many are convinced that, upon his first return, Christ will remain on earth, but others are of the opinion that he will appear for only a short while—to establish his kingdom—and then again withdraw into heaven. According to Piscator, Alsted, and the like, Christ’s rule in the millennium will be conducted from heaven.”12

Taking these two problems together, Riddlebarger summarizes that “the thousand years with glorified men and women revolting against the visible rule of Christ when Satan is released … A fall of glorified humanity into sin after Christ’s second advent means that eternity is not safe from the apostasy and the spontaneous erruption of sin in the human heart.”13 Interestingly, Gentry (a postmillennialist) calls Riddlebarger to task here: “This is not what dispensationalism teaches. Those who are corrupted are mortals who came through the great tribulation into the millennium.”14 As far as I can tell, this is a distinction without a difference. Even if we amend the concept of these people being “glorified,” the fact is that they would have all had to have lived the duration of the thousand years.

4. Premillennialism has the resurrection of the righteous and wicked separated by 1000 years, when Scripture treats them as one event.

Turretin made this a main heading of his final section in the Institutes: “Besides the universal resurrection, is there a particular resurrection of the saints or of the martyrs which will precede the last by a thousand years? We deny.”15

Couldn’t the premillenialist reply to the use of texts like John 5:28-29 by citing the principle of prophetic perspective (i.e. dual fulfillment)? In other words, that Christ speaks in the manner of the Hebrew prophets here as well—so that the raising of the righteous can be separated in time from the raising of the wicked? My reply is that they can try, but it is rendered most improbable by Jesus’ own separation of time between “the time is coming and is now here” (v. 25) versus “the time is coming” (v. 28). Moreover, one has to account for all of the other passages about the return of Christ and all of its features. The weight of evidence that this is a single day is overwhelming.

Some will say that the the Final Judgment of the righteous, that is, the righteousness of rewards, will be stretched out for the entirety of the thousand years. But at that point one is engaged in fanciful speculation.

5. In Premillennialism, the kingdom come in the First Advent must be reduced or explained away.

Ladd’s premillennialism—what he calls “moderate futurism”16 as distinguished from dispensationalism, which he calls “extreme futurism”—seems to overcome this. One could argue that all that the amillennialist means by the spiritual reign of Christ and the church from heaven is present in this inauguated “future” in the present, but with the added benefit of the later physical manifestations of earth. But this still seems to double the time where things are not perfected.

One result is the same sort of pessimism that was later ascribed to amillennialism. So Dabney chiefly aimed this critique at “Pre-Adventists,” as he called them:

“Incredulity as to the conversion of the world by the ‘means of grace,’ is hotly, and even scornfully, inferred from visible results and experiences, in a temper which we confess appears to us the same with that of unbelievers in 2 Peter iii : 4 : ‘Where is the promise of his coming?’”17

Even historic premillennialist—it is said by some—has a carnal, Jewish kingdom in the backdrop. Those early church fathers, often making an anti-Jewish polemic, were operating off of their opponents set of assumptions about the kingdom. As Bavinck said about the Jewish view of late Antiquity:

“In Jesus’s day Israel expected a tangible, earthly, messianic kingdom who conditions were depicted in the forms and images of Old Testament prophecy. But now these forms and images were taken literally. The shell was mistaken for the core, the image of it for the thing itself, and the form for the essence.”18

Not only is there no clear biblical text showing Christ to reign on earth again until the Last Day, but other texts speak of the opposite necessity: “Jesus, whom heaven must receive until the time for restoring all the things about which God spoke by the mouth of his holy prophets long ago” (Acts 3:20-21). Can “all things” here be restricted to commencing a future Jewish kingdom, or must it not mean all things literally being restored? There is nothing in the logic of the case that necessitates such passages be about anything but the ultimate future state.

_________________________

1. Ladd, The Presence of the Future, 140.

2. Ladd, The Presence of the Future, 139.

3. Ladd, The Presence of the Future, 152.

4. Ladd, The Presence of the Future, 95.

5. It should be noted that most of Ladd’s citations are from apocryphal books and then he adds, “Daniel stands apart from the later apocalypses in that this pessimistic note is strikingly absent” (The Presence of the Future, 97). Whether canonical apocalypses can be distinguished from the non-canonical along these lines must be studied further, but, needless to say it would be in the interest of the postmillennialist to demonstrate this.

6. Michael Vlasch, “Is Revelation 20 the Only Supporting Text for Premillennialism?” Blue Letter Bible.

7. Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1994), 1129.

8. Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, IV:656.

9. cf. Turretin, Institutes, III.20.3.3.

10. Turretin, Institutes, III.20.3.7.

11. This is the descriptive used by Boettner in The Millennium, 20.

12. Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, IV:657.

13. Riddlebarger, A Case for Amillennialism, 232.

14. Gentry, He Shall Have Dominion, 75.

15. Turretin, Institutes, III.20.3.

16. Ladd, A Commentary on the Revelation of John, 12.

17. Dabney, Systematic Theology, 840.

18. Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, IV:655.