Prophetic Realism

Having examines the four prevailing models of interpreting New Testament prophecy, especially Revelation—preterism, futurism, historicism, and idealism, I now turn to my own view. As with all theology I believe that the basic metaphysical outlook of the classical period, from Plato and Aristotle down through the early Christian thinkers, with giants such as Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, and which was embraced by the early Reformed tradition—that this outlook was the only rational way of looking at the world. All we are doing here is applying the same to eschatology. The doctrine of last things cannot be the one thing that “sticks out” of a most rational way to view all things.

Now this is a paradoxical claim, but I will make it. On the one hand, the study of metaphysics that would so enrich this perspective does take some rigorous thought, and is certainly not for everyone. On the other hand, the results of it are something that I believe most simple Christians already believe, even if they can’t quite explain why they believe it.

I think that, instinctively, most Christians have a hard time buying any one of the four interpretive views (preterism, futurism, historicism, and idealism), and for a very good reason. They are truncated views. They are trying to explain the whole show where they plainly cannot.

I think that this incapacity is plain to most believers. What most do in reaction is to simply turn away from the study of eschatology, and the few that don’t turn back, dig their heels in to embrace something that is frankly narrow to the point of incredulity. Realism is the way to view the whole.

However realism is also, first and foremost, a view of metaphysics. And the Scriptures were written to all believers for our practical benefit. We know that this does not mean that all parts of the Scripture will be equally clear to us. If this is all too mind-splitting (or hair-splitting), I would encourage anyone to just skip it and think of idealism as the view closest. In truth, idealism’s emphasis on the objects of Revelation being spiritual imagery is quite correct. But what are the symbols of essentially? This is where idealism’s attempt to be an “alternative” to the other three views can relegate these spiritual things to, well, non-things. I maintain that they are the reality (hence: realism) to which the earthly examples conform.

As a last introductory note, I should say that there was a school called “prophetic realism” within biblical scholarship in the mid-twentieth century. But as one would expect, within the flow of modern thought, this “realism” meant the exact opposite of classical realism. In fact, it was materialist. The idea was meant to be in direct opposition to Albert Schweitzer or really any futuristic and apocalyptic definition of the kingdom. The kingdom was entirely in history. Thus it was called “realist” because it was “real,” that is, in the concrete world of material particulars.1

A (Very) Brief Introduction to Realism

Realism is the belief that universals are real things (res). What are universals? At first these are conceived as “ideas,” such as beauty, goodness, justice, and truth. These are not merely useful names for abstract nothings, but rather objects of an invisible, immutable, eternal nature. Nominalism, by contrast, holds that a universal is merely a name (nomen) that we supply in order to assign meaningful predicates to individual things.

Although this was very much a medieval philosophical debate, the roots of it go back to ancient Greece. As Plato’s dialogues famously attempted to show, unless there is an eternal form of Justice, for example, then our use of the concept to describe particular instances of a “just war,” a “just law,” a “just ruling” and so forth, is really a matter of subjectivism.2 Unless the idea we have is of some eternal reality—more real than the instance that the adjective (e.g. “just”) is describing of the changeable phenomena in time—then none of the predicates in any sentence we utter are objectively meaningful. At the very least, none of the objects we are talking about in a narrative flow would be about anything beyond themselves.

With nominalism, the mind loses unity to the diversity of things we see. It is unclear what objective meaning any of our words possess if the term signifying any referent does not possess greater existence than the particular instance.

When Augustine and, then later, the Medieval Scholastics, appropriated these ideas within the superior context of Christian theology, these universals were now seen to be two things: 1. attributes of God and 2. ideas in the mind of God.3

The Reformed Scholastics naturally found agreement and disagreement with the medieval schoolmen, but the basic classical metaphysical outlook was taken for granted.

One of the main areas of theology where this shows up among the Reformed is in the area of prolegomena: specifically when it comes to the question of the manner of our knowledge of God. Is it archetypal or ectypal? Following Duns Scotus in the Middle Ages, Franciscus Junius defined archetypal theology as “the wisdom of God Himself … essential and uncreated,”4 or “the divine wisdom of divine matters.”5 In short, it is the knowledge of God as God knows Himself. Clearly, then, only God can have archetypal knowledge of God. Notice the word is a construct of the Greek words arche and typos.

The same Reformed Scholastics then spoke of ectypal theology. The word comes from the preposition ek, meaning “out of,” so that this was like the wax or clay impression from a seal. This was “nonessential and created … as a certain copy and, rather, shadowy image of the formal, divine, and essential theological image.”6

A crucial verse in Romans 1:20. We tend to think of this as a general revelation passage, and so it is. But the principle of the invisible things of God being known through things in creation, when we think about it, obviously also applies to all of the created things spoken of by the Bible as well. The Creator-creation distinction does not cease to be the great division simply because it is special revelation versus general revelation.

This implies not only that all our knowledge about God is analogical, but that all such knowledege exists within one unified hierachy. Some things are more necessary than other things, more foundational than other things; such that what is more foundational and necessary begin to function much like universals, and their appearances in time the particulars. Think of species in relation to their genus. So, for instance, there is one invisible church, yet many visible and local expressions.

The realist is the one who sees the immaterial, more abiding essence as the thing itself, the thing which explains the lesser instances, the thing that brings the unified picture.

Typology is Already Realist

Now to a concept more familiar to us. We all know what types are. However, we are used to thinking of them only as a left-to-right phenomenon. What we will see is that they are more fundamentally a heaven-to-earth phenomenon—and that this is precisely what guarantees their left-to-right progress.

A type is word, concept, thing, person, or event that serves as a symbol or pattern for something greater. Paul’s use of “example” in 1 Corinthians 10 uses the Greek word typos, so that a type can be moral action as well. That is can be exemplary shows us the legitimacy of application of ancient narrative to modern life. But it also starts to build into us the idea that all such things are repeatable phenomena in principle.

The New Testament book that most clearly draws this concept out is Hebrews. Sidney Greidanus writes, “More than any other New Testament writer, the author of Hebrews is known for his use of typology. Although he uses the word ‘typos’ only once, he indicates types with other words such as copy or sketch (hypodeigma, 8:5; 9:23; antitypos, 9:24), shadow (skia, 8:5; 10:1), and symbol (parabole, 9:9).”7

In his excellent little commentary on The Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews, Geerhardus Vos sees 10:1 as a crucial passage:

“the law has but a shadow of the good things to come instead of the true form of these realities.” That expression, αὐτὴν τὴν εἰκόνα, may also rendered “the very image.”8

So if the Old was full of the copies, what can it mean that the New contains still images? Vos answers by considering how an artist first draws a sketch (skia) and then the final picture (eikoon). Note that “both the sketch and the real picture are only representations of some real thing which lies beyond both of them. This real thing would then be the heavenly reality.”9

The upshot for Vos may strike some as too Platonic, but the author of Hebrews has the real heavenly essence “shadowing down” all earthly exemplars (Old and New), while the Old still drives (left to right) toward the New. Hence there are past ectypes, present ectypes, and future ectypes, all of which are participations of the eternal archetypes.

The three texts in Hebrews 8:5, 9:23-24 —

“They serve a copy and shadow of the heavenly things … Thus it was necessary for the copies of the heavenly things to be purified with these rites, but the heavenly things themselves with better sacrifices than these. For Christ has entered, not into holy places made with hands, which are copies of the true things, but into heaven itself, now to appear in the presence of God on our behalf.”

Note that he does not merely say “of the future things,” which would be true in one sense, but not in the sense that he means it. Neither the sketch nor the copy are the ultimate object of reference. So, neither (i) the Levites old altar nor even (ii) the wood used by the Romans for the cross was that essential ground of the sacrifice.

Other Examples and the Link to Symbolism in General

Think of Christ as the Vine and the “forever” promises of the Abrahamic Covenant. One of these is a physical thing—a living organism, but a physical, sensory thing nonetheless; while the other is a concept: a duration of time that never ends. Now, in keeping with what we have seen about the essence of things in eternity, versus their material instances or example, let us ask about both of these:

What is the essence (form) of the Life of the Vine and Forever? If we go back to passages like Psalm 80:7-11, Isaiah 5:7, Jeremiah 2:21, 5:10, and 12:1; Hosea 10:1, and seveal places in Ezekiel, we have the vine representing Israel as an entity and, futhermore, Israel being rooted in the land. What Jesus does in John 15 is to reveal more of the heavenly reality that He was and remains the substance of the “soil” and the whole vine that God’s people are rooted in.

And it doesn’t take too much imagination that the same sort of movement is happening as progressive revelation opens up to us the essence of what “everlasting” meant in the everlasting covenant. Before “eternity” can mean something secondary like “everlasting” in terms of a linear plain—because that’s not what it means in God; God transcends time altogether.

Likewise with its related word forever. Storms, borrowing from other authors, summarizes that,

“on occasion, ‘forever’ can ‘designate something that is true presently and lasts indefinitely into the future, without interruption and without end’ (as, for example, when the Psalmist declares: ‘Your testimonies are righteous forever,’ Ps. 119:144). But in countless other texts, notes Brent Sandy, ‘forever,’ ‘may or may not begin immediately, may be interrupted for long periods of time, and may achieve its perpetuity only in the distant future, when time essentially will no longer matter anyway.’”10

What is the upshot? The upshot is that the “appearances” of the vines in the flow of the text, and of the mentions of the everlasting nature of the covenant (explaining even the sharp contrast between the hopelessness of Psalm 88 and revival of the language of “everlasting” in Psalm 89), are conforming to the pattern of the essential reality in heaven. Each are either increasingly participating in being, or being deprived of being, as they fall away as shadows.

Eternity is breaking into our timeline in a way that we can understand. This reminds us of the great practicality of symbolism. Symbolism (like a whole parable) can both obscure and clarify. Bauckham writes that, “Prophecy can only depict the future in terms which make sense to its present. It clothes the purposes of God in the hopes and fears of its contemporaries.”11

The “Typology” of Types

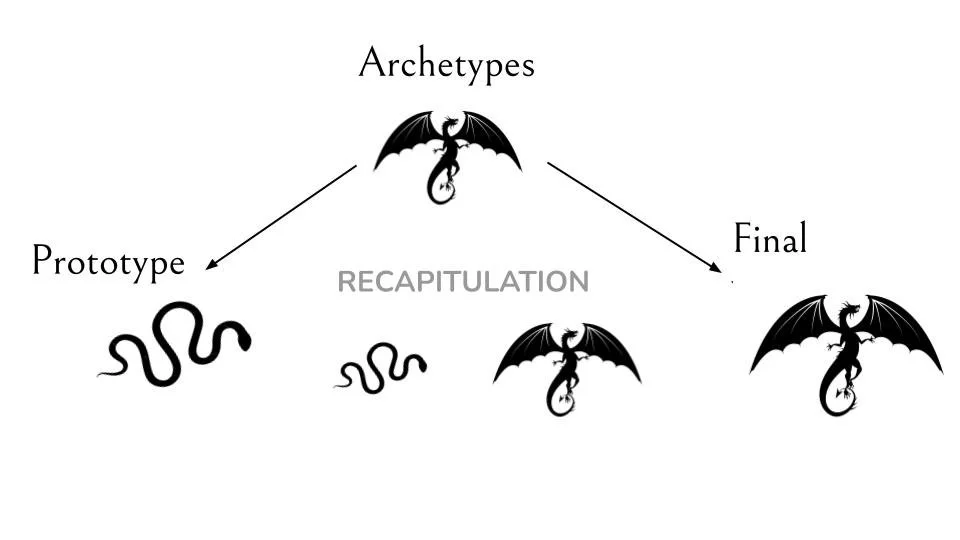

Imagine a chart in the form of something like a compass (or a clock)—but those analogies fail, so let’s just call it a “typology.” First, classical theology’s division of archetypal (above) and ectypal (below) knowledge. Second, biblical theology’s flow from types (left) to antitypes (right). The perspectives—e.g. idealist, historicist, preterist, futurist—are no longer to be thought of as alternative systems, but as aspects of one unfolding reality, which is why there is so much double fulfillment, such most Christians already believe.

The idealist perspective is the archetype or essence of each action, agent, event, or object. The preterist perspective is simply the initial fulfillment at the First Advent. The historicist perspective, the occasional recapitulation of the same to test the church through its whole life. And the futurist perspective the last (and most intensified) fulfillment at, or leading up to, the Second Advent.

As suggested, with the demise of the classical realist vision in metaphysics, these four points spun away from each other as a fractured universe, issuing forth into four competing visions of eschatology, and ways of interpreting the book of Revelation in particular. In point of fact, these four are not to be regarded as four “options” for the way things are or will be, but rather four different aspects of what is in all things, whether past, present, or future, and always bringing about on earth as it is in heaven. All the ectypes would lose meaning without participation in the archetypal essence.

Signs are types, but of what? Signs are not ultimate. By definition, they are not the substance in which they participate. Hoekema rightly wanted to explain “the signs of the times” in light of the already-not yet tension that pervades all New Testament prophetic sections. He said,

“these signs partake of the already-not yet tension since they point both to what has already happened and to what is yet to come … Though these signs leave room for a future climactic fulfillment just before Christ’s return, they are of such a nature as to be found throughout the history of the New Testament church.”12

Many examples could be given. Perhaps the best approach at introducing the concept is to use something that is somewhat uncontroversial from an eschatological point of view.

The Temple as a Test Case

Though many have written on this subject, perhaps no one more profoundly in recent years than G. K. Beale. An important foundational premise is that Israel’s earthly temple was a reflection of the heavenly (or cosmic) temple. The “pattern” of Exodus 25:9;13 may be likened to an architectural blueprint, or (in the language of the philosophers) the formal cause, of the tabernacle. But what exactly are those “dimensions” in the mind of God or in “the space” of heaven, if we can use “space” in that way? To put it another way: What is the being of the blueprint?

This is not only true as a “vertical reflection,” but, as heaven and earth were originally (and ultimately) designed as a unity, so this pattern is actually a microcosm of heaven-and-earth. There are boundaries because, given sin, there are now obstacles between God and man; and, for that same reason, between man and man (cf. Eph. 2:14-15). Beale divides that earthly temple-type into three parts:

“(1) the outer court represented the habitable world where humanity dwelt; (2) the holy place was emblematic of the visible heavens and its light sources; (3) the holy of holies symbolized the invisible dimensions of the cosmos, where God and his heavenly hosts dwelt.”14

Later on the Scripture says, “He built his sanctuary like the high heavens, like the earth, which he has founded forever” (Ps. 78:69). Divine and human actions in the tabernacle reflected the essential, such as the cloud that filled it (e.g. 1 Kings 8:10-13; 2 Chr. 5:13-6:2). The reference to “the ‘cloud’ in Ezekiel’s vision confirms this, since there the word refers both to visible meterological phenomenon and the invisible presence of God in the unseen heaven.”15 Beale argues that even all of the dimensions of the priest’s attire symbolize aspects of the cosmos.16

Details in the design of the temple reflected this—both images of angelic beings (of heaven) and images of the life of the garden (of earth)—cf. 1 Kings 6:18, 29, 32; 7:18-20, 22, 24-26, 42; and then, even some images where heaven and earth most closely overlapped, such as lampstands made of trees (1 Kings 7:49).

Note the realist view in toward this. There is an essence and there are examples of the temple.

The Garden of Eden is the Prototype. It is the first of the ectypes that begins to conform to the essential, or eternal, pattern. Beale begins, “Genesis 2:15 says God placed Adam in the Garden ‘to cultivate [i.e., work] it and to keep it’. The two Hebrew words for ‘cultivate and keep’ are usually translated ‘serve and guard [or keep]’ elsewhere in the Old Testament.”17 He adds, “The same Hebrew verbal form (stem) mithallek (hithpael) used for God’s ‘walking back and forth’ in the Garden (Gen. 3:8) also describes God’s presence in the tabernacle (Lev. 26:12; Deut. 23:14 [15]; 2 Sam. 7:6-7).”18

But the stakes couldn’t be higher for Adam. He was made a warrior priest in a potential war (priest-king). The basic duty in 2:15 is immediately coupled to the promise and threat that we place at the center of the covenant of works. Beale continues:

“that priestly obligations in Israel’s later temple included the duty of ‘guarding’ unclean things from entering (cf. Num. 3:6-7, 32, 38; 18:1-7), and this appears to be relevant for Adam, especially in view of the unclean creature lurking on the perimeter of the Garden and who then enters.”19 And later on, Israel’s priests “were called ‘guards’ (1 Chr. 9:23) … as temple ‘gatekeepers’ … (1 Chr. 9:17-27) who ‘kept watch … at the gates’ (Neh. 11:19), ‘so that no one should enter who was in any way unclean’ (2 Chr. 23:19).”20

Even paganism—the earliest religious practices especially—retained the notions of divine presence, obligations like guarding against intrusions of the unclean, human alientation, and the need for appeasement by blood. Any objections to this only prove the point that all such perversions are just that—deviations from a pattern, just as Paul says:

“For although they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him, but they became futile in their thinking, and their foolish hearts were darkened. Claiming to be wise, they became fools, and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man and birds and animals and creeping things” (Rom. 1:21-23).

The vision of Ezekiel is a chief prophetic type. Ezekiel first harkens back to the patterns of Eden and Sinai: “You were in Eden, the garden of God … You were an anointed guardian cherub. I placed you; you were on the holy mountain of God” (28:13, 14; cf. 16, 18). Now Beale argues that this should be viewed as Adam’s fall rather than Lucifer’s, though it is not clear to me that this is necessary even to make his larger point. In any event, Beale argues that the plural “sanctuaries” (7:24) is an allusion to the original tabernacle (Lev. 21:23; cf. Jer. 51:51).

There is also an eschatological anti-temple, or anti-garden. In the end, this will take the form of Babylon having completed its reverse engineered “Garden” with its rebuilt Tower. That is why is has to “fall” in Revelation 18. It falls from the heavens. It falls and is falling. It doesn’t fall all in a moment in time—after all, God’s people are told to come out of her (18:4) because she “has fallen,” past tense, demonstrating that there is still a time afterwards, but more on that later—and yet there is a thunderous final fall in a last instant.

Circling back to the wider biblical-theological study, Beale speaks of the way that the prophets would hold up the growing dominance of ungodly kingdoms in the language of gardens. One scholar he borrows from says, “Such unbelieving empires plant gardens to ‘enjoy the aesthetic without the ethic;’ they ‘collectivize themselves … to seek a community without a covenant’ (Gage 1984: 60-61).”21 So Ezekiel 31:3-16 summarizes Assyria’s attempt at paradise on earth, in fact, its attempt to outdo Eden, a sort of recapitulation of Babel.

Now Christ is the essence of the temple. The central promise of the covenant was that God would dwell with His people. So the first way that the tabernacle is a picture of Christ is that He is “God with us” (Mat. 1:23; cf. Jn. 1:14).

“For the LORD has chosen Zion; he has desired it for his dwelling place: ‘This is my resting place forever; here I will dwell, for I have desired it” (Ps. 132:13-14).

The work of Christ is central. Solomon would build the temple on Mount Moriah, where 1000 years before, Isaac would be a type of sacrifice, where the LORD would provide a substitute; and then 1000 years later, Christ would be that Substitute, being cast out of the city like the scapegoat from the Tabernacle (Lev. 16). So all of the sacrifices symbolized Him as well.

The church is the chief participant in the temple. Unlike the devilish “copies,” this is true participation in the goodness of the temple’s being. Remembering the second section (visible lights of the heaven), the Lord revealed to John, “As for the mystery of the seven stars that you saw in my right hand, and the seven golden lampstands, the seven stars are the angels of the seven churches, and the seven lampstands are the seven churches” (Rev. 1:20).

Beale draws a straight line from Christ as the fulillment to the church’s mission (hence the name of his book). He does this first by a parallel between the Great Commission passage in Matthew 28:18-20 and the last line of the Hebrew canon, 2 Chronicles 36:23,

“Thus says Cyrus king of Persia, ‘The LORD, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and he has charged me to build him a house at Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whoever is among you of all his people, may the LORD his God be with him. Let him go up.’”

Note that there is a ground of authority over all things followed by the the commission, though in the case of the Jews in Persia, it is to return to the land, and rebuild the temple. Though in both, the connective is GO. “Furthermore,” Beale concludes, “if the temple construction of Chronicles is in mind then this is an implicit commission for the disciples to fulfill the Genesis 1:26-28 mandate by rebuilding the new temple, composed of worshippers throughout the earth.”22

Where Beale rightly stresses that this cosmic temple is continual through and beyond time, I think Augustine would say that this is so precisely because it is first ontological in terms of God, and then participational, moving out in the relationship between God and the world.

What about a rebuilt temple in the end times in Jerusalem? Here our realist principle is one more strike against dispensationalism. The idea simply does not conform to the essence of what the temple is. Storms explains,

“Beginning with the incarnation and consummation in the resurrection of Jesus Christ, together with the progressive building of his spiritual body, the Church, God is fulfilling his promise of an eschatological temple in which he will forever dwell. But what about the literal, physical temple in Jerusalem?”

Here Storms visits Matthew 23:38, “See, your house is left to you desolate,” as the fulfillment of Ezekiel 10:18-19 and 11:23.

He concludes, “God forever ceased to bless it with his presence or to acknowledge it as anything other than inchabod (the glory has departed) … It is entirely possible, of course, that people in Israel may one day build a temple structure and resume their religious activities within it … Whether or not this will ever occur is hard to say, but if it does it will have no eschatological or theological significance whatsoever, other than to rise up as a stench in the nostrils of God.”23

We are used to viewing all of this as biblical theology—as a left to right drama—but at every turn we are confronted with something that can only be the case if the metaphysical reality is set above and beyond it.

As I said at the outset, if this is all obscurity to the student of eschatology, feel free to skip it. However I would recommend at least an idealist view, but one in which the symbols are of real spiritual things—things in heaven more real than those events and persons in history that are copying the pattern.

_____________________

1. cf. George Eldon Ladd, The Presence of the Future (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974), 15-17.

2. In Aristotle’s realism, contrary to Plato, (1) universals (or forms) exist in objects of the mind, but not in any other immaterial realm of ideas; (2) every form always has its matter; (3) these exist independently of our perception of them; (4) these are known a posteriori, abstracted from the sense perception of those externals; but in agreement with Plato, (5) such abstract and objective knowledge is the foundation of our knowledge of reality.

3. F. C. Copleston, Medieval Philosophy (New York: Harper Torchbook, 1961), 20.

4. Francisus Junius, A Treatise on True Theology (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2014), 104.

5. Junius, A Treatise on True Theology, 107.

6. Willem van Asselt, Introduction to Reformed Scholasticism (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2011), 124.

7. Sidney Greidanus, Preaching Christ from the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999), 219.

8. Geerhardus Vos, The Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1956), 55.

9. Vos, The Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews, 55.

10. Sam Storms, Kingdom Come, 27-28

11. Richard Bauckham, The Climax of Prophecy: Studies on the Book of Revelation (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1993), 450.

12. Anthony Hoekema, The Bible and the Future, 70.

13. cf. Exodus 25:9; 26:30; 27:8; Numbers 8:4.

14. G. K. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004), 32-33.

15. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission, 37.

16. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission, 39-45; 47-48.

17. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission, 66-67.

18. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission, 66.

19. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission, 69.

20. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission, 69.

21. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission, 126.

22. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission, 176-177.

23. Storms, Kingdom Come, 19, 20.